Tips + Tricks

Expert mix engineers give their advice on building strong partnerships with artists

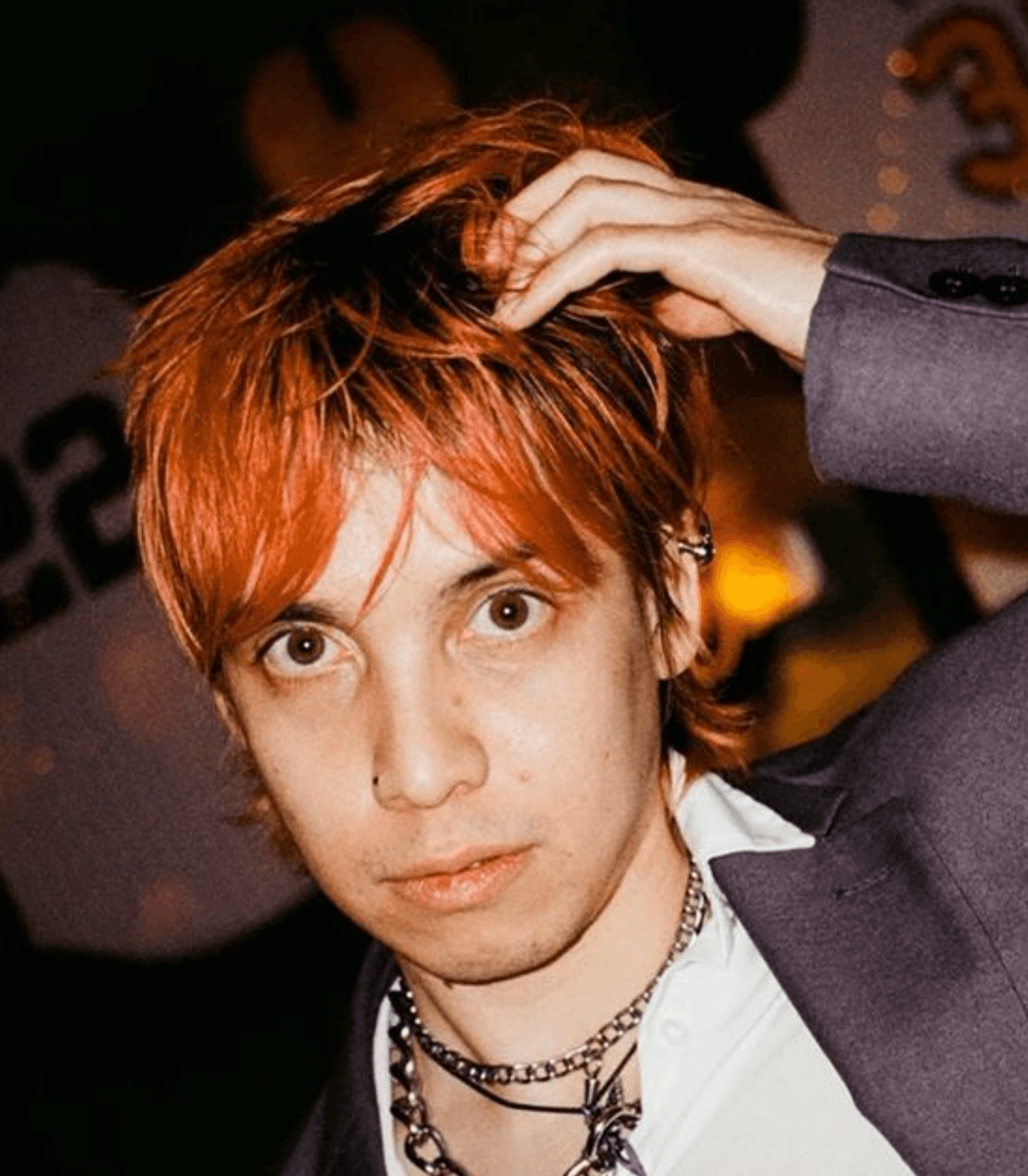

Kenneth Herman

Posted

July 10, 2024

“The mix is too wooly.” “Can you make this sound more like Coca-Cola and less like Ginger Ale?” “Can you make this folk song sound more like this jazz record?” “Why does this mix not sound like this fully finished reference song?” As a mix engineer, you’ve heard it all. The demanding, the confusing, the articulate, the inarticulate, the extremely vague and the over-specific - feedback. The mix notes. The 4AM email the night before a deadline.

The relationship between client and mix engineer is a dance. Communicating with an artist and navigating that back-and-forth dialogue to bring their vision to life is as important as knowing compressor thresholds or dialing in a Pultec. We’ve pulled in a panel of three professional mix engineers across genres and styles, including:

Shane Lance, a producer and mix engineer based in Los Angeles, who has worked with artists like HOLYMAMI, BC Tray, and VANÈS and has built a following on TikTok and Instagram for their mixing and artistic advice.

Sendai Mike. a producer and mix engineer based in Seattle who has worked on records by Ted Park, Tone Sinatra, and 10 Thousand Rats known for their creative videos on vocal mixing.

Will Owen Bennett, a mix engineer and producer based in New York City who has worked with Solomon Rex, Michael Go, and executive produced and mixed Backxwash’s Polaris Award-winning album “God Has Nothing to Do With This, Leave Him Out Of It.”

We’ve pulled together their best insights into how you can create the most out of your collaborations with your clients.

Create an open dialogue from the beginning.

Before any mixing starts, before any stems are processed and before you even open up your DAW, begin an open dialogue with your client. Talk through their vision, get a list of references, and try and paint a full picture of what they’re looking for in their mix. Sendai Mike suggests doing this over the phone rather than email or text.

“Always start with a phone call,” he says. “Get a sense for the feel for the person, their level of technical understanding, and also their expectations. Get all of that information to know what their expectations are sonically.”

Likewise, Shane Lance suggests setting expectations from the beginning and the often laborious process that a mixdown requires. Whether in-person or remote, Shane likes to also speak to an artist directly to introduce the multi-step process it usually takes before they’re happy with a mix.

“In a healthy way, I try to train the people I work with to be open to disappointment,” Shane explains. “The initial version of a production or mix just might not be there. I tell them ‘you have to be okay with one, or two, or three layers of potential disappointment until you get the gold.”

With your phone call or in-person conversation out of the way, make sure to get your artist references in. Request your artist to send stylistic or sonic references similar to their song. Sendai Mike also suggests asking for a demo mix from the artist of their song - they’ll likely want something pretty close to what they already have.

Communicate, communicate, communicate through confusing or unclear notes.

So you’ve gotten the song and you’re in the weeds mixing it. Say the artist is sitting in on the mixdown session, or you’ve completed a first pass and they’re emailing you or texting you notes. What do you do when their notes…are…well, kind of confusing? What if they gave you a reference track that was warm, wide, and vintage but their note is to make it edgier and brighter and more modern? What if they ask for things like “make it more like water” or “make it feel like halcyon” and you don’t know what any of it means?

“I tell the artist to talk at me,” Will Owen Bennett suggests. “I ask them to give me more information than I think I need.” Every artist has their own style of communication, and Will recommends meeting them at their level. “The first thing for them to do is try and explain it in whatever words they have, or whatever vocabulary they know. My job is to parse that.”

Likewise, Shane suggests to keep asking questions. “Keep asking questions and confirming things like - maybe they’re describing it one way, but they mean something else. Maybe by ‘open’, they mean more presence. Try and bridge the gap between what they’re saying instead of getting caught up on semantics.”

Everybody has a different communication style. Some artists are more articulate over email, some over text, some over voice notes. But when things are unclear, Sendai Mike says to always just get on the phone. “If me and a client are going up and down and up and down on this,” he says, “it’s time to get on the phone again and hash it out. Sometimes it just takes one more fix.”

Don’t lose sight of the goal here. You want to make your client happy. “Their vision for the song is the right thing,” Shane says. “It’s my job to figure out their vision and translate it to the world in a way that maintains that, but makes it commercially ready too.”

But what do you do if this part of the process becomes so log jammed it becomes tense or difficult?

Don’t take it personally.

Sometimes feedback hurts. Sometimes you work so hard on a song and you pour hours and hours and hours into it and the artist isn’t happy. Maybe their notes or feedback can feel personal. But above all, don’t lose sight of the goal here.

“They just want the song to sound good,” Shane contends. “They’re not questioning you. Sometimes when someone sends mixed notes it could feel like they’re insulting your mom or something. Like they’re questioning your being or your identity.”

The point, Shane continues, is to take their feedback and use that to drill closer and closer to the artist’s vision of the song. “Sometimes,” Shane says. “It just means you haven’t gotten it yet. So just keep asking questions.”

Usually, Sendai Mike says, the point of contention is typically where the song is almost there but not quite there yet. “Conflict can happen when we’re converging towards the final product and the artist suggests something out of left field.” It’s at this point that it’s important to push back on endless, last minute changes. “We’ve already committed this far to these decisions,” Sendai Mike says. “That’s when I usually push back.”

Sometimes it’s just about setting realistic expectations with clients who may not understand where your work begins and their work ends. “I always tell an artist that you could hire the person who mixed the record we’re referencing,” Shane says. ”And still it’s not going to feel quite right. There are 10 universes with 10 different versions of this mix each and we’re going to have to discover the one that’s in your head together.”

At the end of the day, it’s not about your skill and capability as a mix engineer. It’s about the artist, and their vision and project. “The music is their baby,” Will says. “You need to treat their art, the way they think about it, and how close they hold it to their heart with care.”

If there is a disconnect between what they want and what you’re capable of, just try to meet them where they are, Sendai Mike says. “Meet their expectations as best as you can both sonically and energetically. It’s important for everybody to feel good about the song.”

If it comes down to any friction between what the artist wants and what you think is best, just communicate your decisions and why you made them. “Speak up honestly,” Shane suggests. “Ultimately it’s my job to bring their vision to fruition. But I’m going to stand behind my decisions and hope to help them understand it.”

When disagreements arise, the best way to navigate them is to always create a good working environment.

Create a good vibe in the studio.

You and your client are making art. You’re working on a project meant to entertain and bring joy, sadness, excitement, euphoria, awe, or inspiration into a listener. Don’t lose sight of that in the minutiae of turning knobs. That all begins with creating a good working environment for you and your client.

“Create a safe space,” Shane says. “A creative space where you can throw out ideas and they won’t be shot down as stupid.” The point is to foster an environment where disagreements and communicating ideas back and forth is encouraged. “You gotta be open to someone giving an idea you don’t love and also feel free to give out an idea that in the end might not work.”

When an artist trusts you, they’ll be receptive to your changes. They key to building that trust is to make the artist feel heard, Will says. “If the person feels listened to and feels like they’re taken seriously and not being dismissed,” he explains, “then they’re going to trust you a lot more.” With the trust built in, the artist will be more receptive to your changes. “Once you foster that environment, they’re going to take your suggestions a lot more seriously.”

And have fun, Shane explains. “We gotta make this thing a vibe,” he elaborates. “The goal isn’t to just recreate this reference we have. It’s not just some practical goal or we’re here to just get business.” The goal instead, is to have fun making a song so much so a listener can hear that in the final product. “Create a space that feels fun. You want to feel something [in the studio] and hope the listeners feel something too.”

With a good space, you can almost guarantee repeat business.

On growing your business and keeping your clients coming back

So you’ve delivered your mix and the artist is satisfied. What’s the key to get them coming back or suggesting you to others?

“Reliability is number one,” Will says. “Doing what you’ll say you’ll do when you say you’ll do it. More important than just basic [mixing] competency is being communicative and just being a joy to work with.”

The music industry is built on relationships. That said, the relationship between mixer and artist is very important, Mike says. “Have a relationship and just learn,” he elaborates. “Learn their sound, learn their tendencies, and anticipate their vision. The closer and better you’re working together, the better.”

Be collaborative and open, Shane says. “It’s on us producers and engineers to be really gracious and open and know that we’re really hired to serve.” He continues, “it’s best if it’s collaborative. You’ve been hired to bring their vision to fruition and you’ve got to serve that vision humbly.”

If you build a relationship on trust and validation, then clients will stick around, Will says. “There are lots of people who are good mix engineers,” he explains. “But if you take someone seriously, if you’re able to understand and apply their vision, then people are going to keep coming back to you.”

Communication is key.

All of these professionals agree - communication is the most important element of the mix engineer and artist relationship. More than knowing your EQ curves, more than gain staging, more than great plugins.

Thankfully with Highnote, communication is as easy as one link in an email.

Highnote is the all-in-one file organization and messaging platform for audio collaboration. You can upload each of your mixes and discuss revisions, changes, and feedback in real-time with the Spaces function, as well as A-B test different versions with your mix engineer.

Good luck on your next session.

Published in

Tips + Tricks

File under:

Client Management

Feedback

Mixing